Natural Log Calculator

The natural log calculator (or simply ln calculator) determines the logarithm to the base of a famous mathematical constant, e, an irrational number with an approximate value of e = 2.71828. In other words, it calculates the natural logarithm.

But, what is the natural logarithm, ln x, of a given number x? This is the power the number e has to be raised to in order to result in a given number x.

How to use the natural logarithm calculator

Like all other logarithms, the natural logarithm of x returns the power, or exponent, to which a given base e must be raised to yield back the number x. It is easier to understand this notion when the base is an integer, for example, 2 or 3:

log₂ 16 = 4 since 2⁴ = 16

log₃ 81 = 4 since 3⁴ = 81

By the way, do you know that all the logarithms are multiples of each other? To understand this better, access the article "Change-of-base Formula Made Easy".

In the case of the natural logarithm, this is somewhat less intuitive because its base, e, is not an integer. But, since the value of e is between 2 and 3, we understand that e⁴ has to be somewhere between 2⁴ = 16 and 3⁴ = 81.

It turns out that e⁴ = 54.498. This equality can be stated in terms of the natural logarithm in the following way, which you can check by using the ln calculator:

ln 54.498 = 4

Here are some examples of natural logarithm:

- ln 1 = 0 since e⁰ = 1

- ln 10 = 2.3026 since e2.3026 = 10

- ln 20 = 2.996 since e2.996 = 20

- ln 50 = 3.912 since e3.912 = 50

- ln 100 = 4.605 since e4.605 = 100

You can check out the correctness of the above results by using our natural log calculator and the exponent calculator.

Additionally, to better grasp the interplay between the exponential and logarithm functions, you may want to check the exponent calculator along with the log calculator.

Other ways to denote the natural logarithm

One way of denoting the natural logarithm is loge. This is the same as when we write the logarithm to the base two as log₂.

But, a more common way to write the natural logarithm is ln, which is an abbreviation of the Latin expression logarithmus naturalis, the name the natural logarithm was given when the Latin language was still the lingua franca of science.

There is also a third way of writing the natural logarithm: log. This notation is somewhat problematic, though, as it is often mistaken for the logarithm to the base 10. However, this is the syntax many software implementations of natural logarithm use, so be careful!

What's so natural about the natural logarithm?

Why exactly does ln x deserve to be called natural? Maybe the most important property of the natural logarithm is that it is the inverse function of the exponential function eˣ, the only function whose rate of change, or the derivative, is precisely itself: (eˣ)' = eˣ.

In simpler words, the exponential function eˣ governs its own rate of change, which in some sense makes it self-sufficient and not dependent on any other function to define the way it changes. Exactly this property makes both eˣ and its inverse function ln x the natural choice when describing many real-world phenomena.

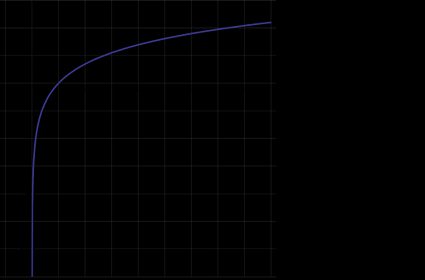

The natural log graph

Another interesting property of the natural logarithm is how it changes its values as the argument x increases. One way of expressing this is by stating that the derivative of the natural logarithm is inversely proportional to its value x, which can be written as (ln x)' = 1/x.

You can also observe this property by looking at the graph of the natural logarithm. Although it increases as the value of x increases, the rate of growth is getting smaller and smaller as x approaches higher and higher values:

Where did the number e come from

At first glance, you wouldn't say that the number e bears any importance to the endeavors of humans or nature. But this is not so! It happens that this number is one of the most important constants in mathematics, so much so that it deserves a proper name. It is called either Euler's number or Napier's constant, depending on whom of these two great mathematicians one wants to attribute its discovery.

Nevertheless, it seems that Leonhard Euler (1707 - 1783) did get more credit, based on the fact that the very letter Euler used to denote this constant is how we denoted it today. Although Euler was the first to calculate e to a significant number of decimal places, he wasn't the first one to discover it: read more about it in the next paragraph.

How to make e amount of money

Swiss mathematician Jacob Bernoulli (1654 - 1705) stumbled upon the existence of the number e when tackling the problem of compound interest. Let us first understand the idea behind simple interest. For a given initial sum of money, say 1 USD, you want to know how much you will have after one year has passed if an interest of 100% is credited only once and at the end of the year. The answer is easy: 2 USD (you can verify it with the simple interest calculator).

But, with compound interest, things get a bit more complicated. For example, if the same interest of 100% is now split into two equal parts of 50% and credited twice, 50% at the end of the first six months, and another 50% at the end of the year, then the final yield is obtained by using the formula

1 × (1 + 1/2)² = 2.25 USD

(learn why with our compound interest calculator).

Furthermore, if the interest of 100% is split in weekly lumps, you would have the final yield of

1 × (1 + 1/52)⁵² = 2.692 USD.

Bernoulli asked a simple question: what would happen if compounding was continuous? In other words, what would be the final yield if the interest rate of 100% is split into infinite parts, each credited at the end of an infinitely short period of time?

This problem of continuous compound interest, stated mathematically, boils down to the challenge of calculating the limit of (1 + 1/n)ⁿ as n approaches infinity. It turns out that the result is precisely the number e! Moreover, the above expression may be used as a way to define e. To answer the Bernoulli's question: with continuous compounding, the initial dollar would yield precisely e = 2.718281828 USD at the end of the year!

The real-world importance of ln 2 and other natural logarithms

The easiest natural logarithms to calculate are:

ln 1 = 0 since e⁰ = 1, and

ln e = 1 since e¹ = e.

But, presumably, the most important natural logarithm is the one that calculates the value of a number between 1 and e, which turns out to be the number 2. Using the natural log calculator, we get

ln 2 = 0.6931.

It turns out that ln 2 is also equal to the alternating sum of reciprocals of all natural numbers:

ln 2 = 1 – 1/2 + 1/3 – 1/4 + 1/5 – 1/6 + ...

At first glance, this number appears to have no particular importance whatsoever. But, ln 2, as obscure as it may seem, appears in some pretty significant and, at first glance, unrelated real-world problems.

For example, it has its role in the formula for the half-life of radioactively decaying matter, as shown in our half-life calculator. It is also present in the calculation of time needed to double the initial amount of money if a fixed rate is applied over a given time.

So, if you have 1,000 USD in your bank account, and the bank provides an r = 7% per annum interest rate, you may want to ask yourself how long it will take to double my initial amount. Well, this is where ln 2 comes into play: the natural logarithm formula that calculates the time needed is (100 * ln 2)/r, which can be simplified to the approximate value of 70/r.

Therefore, in the case of r = 7%, you would get 70/7 = 10 years as an approximate time needed for your initial sum of money to double. Similarly, one can get analogous formulas for the time needed for the initial quantity to triple, quadruple, or n-tuple, given a fixed rate of growth over time.

Other applications of the natural logarithm

From the previous paragraph, we may conclude that natural logarithms occur in every process with a period-related constant growth or decay of some quantifiable phenomenon.

Apart from the already mentioned examples of radioactive decay and the problem of yield with a fixed interest rate, natural logarithms appear when calculating the growth and decay of any bacterial, animal, and plant population, the decay rates of a charged capacitor, or the temperature change of an object.

References

- David S. Kahn: Attacking Problems in Logarithms and Exponential Functions, Dover Book on Mathematics, 2015

- Edward Kasner: Mathematics and the Imagination, Dover Books on Mathematics, 2001